Ship of Destiny

Ship of Destiny Golden Fool

Golden Fool Assassins Apprentice

Assassins Apprentice The Dragon Keeper

The Dragon Keeper Fools Fate

Fools Fate Fools Errand

Fools Errand Fools Assassin

Fools Assassin The Mad Ship

The Mad Ship Shamans Crossing

Shamans Crossing Ship of Magic

Ship of Magic City of Dragons

City of Dragons Dragon Haven

Dragon Haven Fools Quest

Fools Quest Blood of Dragons

Blood of Dragons Assassin's Fate

Assassin's Fate Assassins Quest

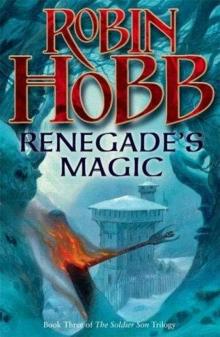

Assassins Quest Renegades Magic

Renegades Magic Forest Mage

Forest Mage Assassin's Apprentice tft-1

Assassin's Apprentice tft-1 Assassin's Quest tft-3

Assassin's Quest tft-3 Royal Assassin

Royal Assassin Assassin's Apprentice (The Illustrated Edition)

Assassin's Apprentice (The Illustrated Edition) Assassin's Quest (UK)

Assassin's Quest (UK) Royal Assassin (UK)

Royal Assassin (UK) FF3 Assassin’s Fate

FF3 Assassin’s Fate Royal Assassin tft-2

Royal Assassin tft-2 Fool’s Assassin: Book One of the Fitz and the Fool Trilogy

Fool’s Assassin: Book One of the Fitz and the Fool Trilogy Fool's Fate ttm-3

Fool's Fate ttm-3 The Golden Fool ttm-2

The Golden Fool ttm-2 The Liveship Traders Series

The Liveship Traders Series The Wilful Princess and the Piebald Prince

The Wilful Princess and the Piebald Prince City of Dragons rwc-3

City of Dragons rwc-3 The Tawny Man 1 - Fool's Errand

The Tawny Man 1 - Fool's Errand Words Like Coins

Words Like Coins The Complete Tawny Man Trilogy Omnibus

The Complete Tawny Man Trilogy Omnibus Farseer 1 - Assassin's Apprentice

Farseer 1 - Assassin's Apprentice The Complete Farseer Trilogy Omnibus

The Complete Farseer Trilogy Omnibus The Soldier Son Trilogy Bundle

The Soldier Son Trilogy Bundle Fool's Errand ttm-1

Fool's Errand ttm-1 Blue Boots

Blue Boots Shaman's Crossing ss-1

Shaman's Crossing ss-1 Mad Ship

Mad Ship Dragon Keeper

Dragon Keeper The Willful Princess and the Piebald Prince

The Willful Princess and the Piebald Prince Ship of Destiny tlt-3

Ship of Destiny tlt-3 Rain Wild Chronicles 02 - Dragon Haven

Rain Wild Chronicles 02 - Dragon Haven The Dragon Keeper trwc-1

The Dragon Keeper trwc-1 The Triumph

The Triumph Dragon Keeper Free Edition with Bonus Material

Dragon Keeper Free Edition with Bonus Material Mad Ship tlt-2

Mad Ship tlt-2 The Inheritance and Other Stories

The Inheritance and Other Stories Tawny Man 02 - Golden Fool

Tawny Man 02 - Golden Fool Farseer 2 - Royal Assassin

Farseer 2 - Royal Assassin Rain Wilds Chronicles

Rain Wilds Chronicles Forest Mage ss-2

Forest Mage ss-2 Ship of Magic lt-1

Ship of Magic lt-1 Renegade's Magic ss-3

Renegade's Magic ss-3